Veritable Michael: a new opera

By Tom Floyd and Sophie Goldrick (of Shadow Opera), and Marion Thain

Fig. 1: Banner image for Veritable Michael - a podcast opera. Design by Tom Floyd and James Long. © Shadow Opera 202.

In May 1884, London awoke to the news of an exciting new playwright and poet bursting onto the scene to rave reviews. Michael Field not only won the praise of the papers, but also piqued the interest of literary giants Robert Browning and Oscar Wilde. But Michael was hiding a secret: he wasn’t a man, he wasn’t a woman — Michael Field was, in fact, two women, deeply in love, writing as one. Despite their early critical success, Katherine Bradley (1846 –1914) and Edith Cooper’s (1862 –1913) renown faded into obscurity after the revelation of their true identities in the press by author Robert Browning. Nonetheless, Bradley and Cooper continued to write and to publish, leaving behind them on their deaths many books of lyric poetry and verse drama, some of which have gained renewed respect and popularity in recent years among scholars and enthusiasts of the period. In addition to the published work, however, they also left behind a 29-volume hand-written diary of Michael Field (held in the British Library) charting the women’s collaborative life, work and passions between around 1880 and 1914. This work tells a story that is intriguing and compelling, and it brings the idea of ‘Michael Field’ to life in a glory of detail.

Tom Floyd and Sophie Goldrick’s opera, Veritable Michael, sets Katherine and Edith’s letters, diaries and poetry to music, and includes spoken extracts of their diaries and contemporary press reviews of their work. The opera was initially created in serialised form as a podcast, including guest interviews with Michael Field scholars. The score won the prestigious Stephen Oliver award for best new opera in 2021, and subsequently a staged version of the opera premiered in 2022. Tom Floyd, Sophie Goldrick and Marion Thain discuss here the experience of writing, performing and witnessing this new work of Michael Field.

Witnessing Veritable Michael

By Marion Thain

As one of the academics consulted during the opera’s formation, and interviewed for the podcast, I had long had an idea of what Tom, Sophie and the opera were about, and I had listened to the whole thing online. I knew that they were not only setting Michael Field’s poetry to music, but also – gloriously and unexpectedly –some of their diary entries. For Bradley and Cooper’s own aestheticisation of their life story through the diary (a highly composed work) to receive this treatment was a genius idea. Yet nothing really prepared me for the experience of seeing the work performed at the debut in the large Thames tunnel shaft at the Brunel Museum in East London in summer 2022. The audience descended a winding metal staircase from the warm August air into a large rusty metal tube under the earth. This vintage piece of Victorian industrial entrepreneurialism set a minimal and somewhat steampunk backdrop for the performance that deracinated us all from time and space for the duration of the music. For a while we were absorbed in Michael Field’s world of passion, plays, poetry and cultural politics. The power of this musical interpretation of Katherine and Edith’s story was immense. Amplified by the surreal bubble of the underground setting, the audience was transported. The wit made possible by the real-life male avatar of ‘Michael Field’ somehow highlighted the pathos of the women’s story, and the opera perfectly captured the way in which Bradley and Cooper’s diaries mixed the humorous, the poignant and the passionate.

I next saw the opera performed at an event we hosted in the chapel of King’s College London. The decorative Victorian finery of the chapel’s interior provided a backdrop diametrically opposed to the minimal metal of the industrial shaft. In this setting, the knowledge of the women’s religious conversion, towards the end of their lives, seemed pre-empted through the story that unfurled before our eyes and ears. The opera was set in a context that seemed to speak of their destiny. The event had a particular resonance because as a Church of England chapel, same-sex couples still cannot be married there – a live issue for many among our staff and students at the College. To witness this same-sex ‘marriage vow’ in a place that is itself a contested space added a wholly different dimension to the event. My experience of the opera was even more powerful than the first time, with the space adding both a premonition of the women’s conversation and something of a shadow over their story, representing as it did the conventions they worked so hard to free themselves from. The comment I heard repeatedly from the audience after the show was that colleagues and friends were so powerfully moved by the work that it raised the hairs on the back of their necks.

If artistic works come to life in a triangulation between creator, performer and audience, then this work has unleashed a particularly haunting alchemy. The experience stayed powerfully with me for some time. I hope it won’t be too long before there is another opportunity to remake that experience and transport once again into Tom and Sophie’s incredible rendition of the lives of two people who (in part because they could have moved through the very performance spaces we sat in) felt close enough to touch.

Fig. 2: Screenshot for promotion video clip for Veritable Michael - A podcast opera. Design by Tom Floyd. © Shadow Opera 2021.

Why Opera? Perspectives on composing Veritable Michael

By Tom Floyd

It may come as little surprise that of all the many creative possibilities opera offers as an artform, rendering biographies with high fidelity of historical detail is not one. It is a daunting task to capture the complexities of one, let alone two complete lives in a written biography, where the constraints of a word count inevitably mean difficult choices must be made about what parts of the subject’s life will be brightly lit in the reader’s consciousness, and which will remain in dappled shade, or complete darkness. The challenge multiplies and morphs once the biography is being presented in play or film form, with the writer, director, designer and actors all now layering something of themselves over the subject. Historical accuracy is compromised, but it’s considered to be a price worth paying in order to touch something more fundamental, or perhaps, in some sense, more ‘true’ than that offered by a mere sequence of facts. In short, let’s not let the truth get in the way of a good story. When we attempt, however, to offer an audience a detailed account of a person’s life in operatic form, we are now in the Kingdom of Canute looking down on some very wet feet. When it comes to capturing history, opera faces all the same challenges listed above, as well as some more mellifluous ones.

The penetrating, psychological and ever-present nature of music within opera means that no matter the source of the words, characters and events, everything the audience is experiencing during a performance is being emotionally coloured by the choices made by the composer. In opera the music is the story, and the story is the music, or as Wagner put it: ‘where music begins, words cease to function’.[1] In opera, the music is the breath of storytelling, keeping it alive and moving forward for as long as it sounds, and not a moment more. It dissolves the boundaries between the inner and outer worlds of not only characters, but also ourselves. Whether we understand the words being sung by a character in any particular moment is not as important as we might think. What is unmissable is the constant and rich source of information being fed to us through the colour of the voices and instruments, effortlessly translated by our brains into a psychological tapestry of intentions, emotions and connections. Audiences will inevitably interpret this musical signal, along with the visual components of a performance, in greatly varying and deeply personal ways. We should keep an eye, or perhaps an ear, on how our emotional response was set in motion when the composer first put pen to paper.

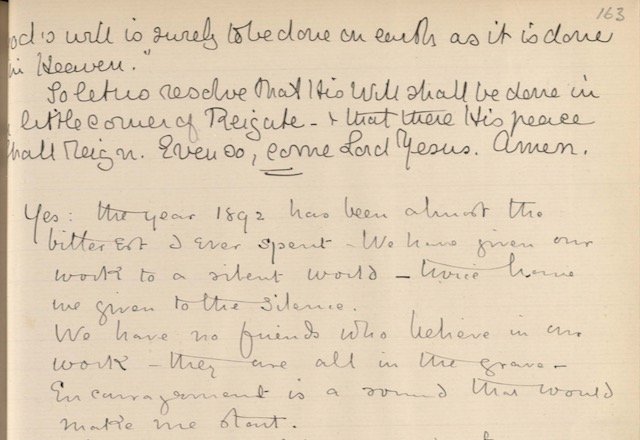

Fig. 3: Katherine Bradley diary excerpt. New Year’s Eve 1892. Accessed via https://michaelfielddiary.dartmouth.edu/page-view/5/332

Veritable Michael makes no attempt to portray the ‘true story’, whatever that may be, of the individual and shared lives of Katherine and Edith. It is instead a poetic impression, a dream drawing on long dead realities, and one collectively dreamed, enjoyed, explored and shaped with my co-creator Sophie Goldrick, soprano Lizzie Holmes, and the academics who guided us: Prof. Marion Thain, Dr Ana Parejo-Vadillo, Dr Sarah Parker and Prof. Carolyn Dever. Every sung word in the opera comes from Michael Field’s diaries, letters or poems. Every scene is based around events detailed in the diaries. However, the emotional landscape of the piece, contoured by the score, and detailed by the artists’ performances, no doubt bears little resemblance to the reality of what it was for Katherine and Edith to live those moments.

Fig. 4: Edith Cooper diary excerpt New Year’s Eve 1892. Accessed via https://michaelfielddiary.dartmouth.edu/page-view/5/333

Shaping the Story

By far the most common creative path composers and writers travel along when writing an opera is something along the lines of: composer and /or writer develops a creative concept (the story); the writer creates a libretto (the words); and finally the composer sets the words to music (the score). This is an oversimplification of what is typically a much more collaborative process, with the composer usually being heavily involved in the structuring and editing of the libretto. However, it’s a useful summary to illustrate the more unusual route Veritable Michael took to the stage.

Having stumbled upon Michael Field’s story and after becoming enticed to explore it operatically, Sophie and I set about reading as much of Michael’s poetry, diaries, letters and biographies as we could lay our hands on. With such a rich mine of material we decided that we would not work with a writer, and instead set ourselves the task of creating our libretto entirely from Katherine’s and Edith’s own words. This led to an extensive storyboarding process mapping anecdotes from the diaries and letters with their contemporaneous poetry, guided and enriched by our conversations with academics working on Michael Field.

We initially conceived Veritable Michael as a stage work. However, the onset of the pandemic in 2020 saw us pivot to planning an audio version. As our research connected us with Michael Field scholars, we felt their contribution should be included in what we were making. This inspired us to make a podcast, curating our opera vignettes with recorded interviews and presented by Sophie.

Our original storyboard had the vignettes taking place chronologically, but we soon moved away from this when we identified that in our telling of the story, the opening night of A Question of Memory (Katherine and Edith’s only play to ever be staged at the Independent Theatre in 1893) served as a fulcrum around which all other events balanced. After a short prologue, we chose to place the action straight into rehearsals building up to this moment, assuring the audience of Katherine and Edith’s artistic capabilities and standing. Time then turns back to the period predating Katherine’s and Edith’s union as Michael Field, moving chronologically forward from then on until we return to where we opened. The intention is that this scene is given greater significance when it comes around for the second time because the audience is aware it is not the continuation of a rising artistic career but the last ditch attempt at saving one.

Fig. 5: Lizzie Holmes (left) as Edith Cooper and Sophie Goldrick as Katherine Bradley in Veritable Michael, The Brunel Museum, 13th August 2022. Photograph by Ruth Knight.

Expressive Time and Space

Despite the many directions composers have taken opera over the centuries, we see composers continuously reinventing the concepts of ‘recitative’ and ‘aria’. Recitative refers to a style of music where the composer has set text to be delivered in a speech-like or naturalistic way. The purpose is to convey information rather than exploring emotion. The music tends to be pared back giving space to allow the character’s text and any plot implications to be clearly understood. Recitatives often move time forwards. Arias (or songs) on the other hand refer to moments of introspection where a character may lyrically express their inner world, with the music empathetically evoking their emotions in the audience. Arias often create a sense of time pausing.

For many composers the divide between these two forms of music is very permeable, but the forces of recitative and aria can be detected nonetheless. Before writing Veritable Michael, I sensed the allocation of recitative, aria, and a form that would sit somewhere in between, could open up some interesting creative possibilities when responding to different sources of Katherine’s and Edith’s text. Given the importance that writing and text plays within our story, the idea was to explore how musical forms could be used to place the action, and the audience, into different theatrical spaces. We came to refer to these spaces as the literal, lyric and liminal.

Fig. 6: Sophie Goldrick as Katherine Bradley and Patrick Neyman as Michael Field in Veritable Michael, The Brunel Museum, 13th August 2022. Photograph by Ruth Knight.

Literal Space

There are many moments in Veritable Michael where we are responding to real events, as described by Katherine or Edith in their diaries. It provided an enjoyable creative challenge to explore ways of musically giving these moments a sense of space such as in the Opening Night scene where we hear a cimbalom in the orchestra, an instrument associated with Hungary, where A Question of Memory is set. The music in this scene plays a shifting but mainly diegetic role, starting with the score providing incidental music to the rehearsal scene before coming into focus as the overture of the play.

Another example of where the music evokes a literal sense of space, albeit in a more poetic manner, is in Scene 4: Edith’s Waltz. In this scene I set an extended excerpt of one of Edith’s diary entries describing her heady but destabilising infatuation with the art critic Bernhard Berenson during their time in Paris. The music draws on Parisian cafe music and makes use of the romantic but unstable nature of waltzes. Unlike the stability of triangles in geometry, in music the three beats per bar of waltzes gives them the feeling of continuously toppling forward. The desired effect is to bring Paris to mind, to give Edith a whimsical backdrop over which to play out the fantasy romance, and to place her in a literal dance with the object of her desire.

Lyric Space

The libretto of Veritable Michael includes several of Michael Field’s poems, and during these scenes the aim of the music is to open a more lyrical space, such as during Scene 5: Michael’s Vow. This scene serves as the climax in the romantic development of Katherine and Edith’s relationship and was the first piece of music I sketched when writing Veritable Michael. It was a part of the libretto I was particularly excited about as it features the poem It Was Deep April (1893), a clear and unapologetic marriage vow, and one where we had found references in the diary to how Katherine had penned it on a train. I knew I wanted to set the poem in a lyrical, emotive style, but I also wanted to play with bringing the sound and energy of steam trains into the musical language. In contrast to the above examples, the music here is not trying to create a literal sense of location but is instead offering the singers a lyrical space to explore the passion of the poem, within a sound world that references the historical detail of its origin. Whether we picture the women on the train or not is unimportant. The real intention of the train-inspired music is to give Katherine’s and Edith’s relationship, and our story, a sense of dramatic propulsion as we move into the final chapters.

Fig. 7: Lizzie Holmes as Edith Cooper (left) and Sophie Goldrick as Katherine Bradley in Veritable Michael, The Brunel Museum, 13th August 2022. Photograph by Ruth Knight.

Liminal Space

The musical space which came into focus last during the writing of Veritable Michael was inspired by the more recitative excerpts from the diaries. Early on I knew I would want to develop a recitative style for some of the diary entries. Recitative felt like the right choice for creating the sense of intimacy and introspection we feel when writing or reading a diary. I wanted to place the audience inside Katherine or Edith’s head, to create the feeling of bearing witness to thoughts taking shape in real time.[2] The earliest examples of this style can be found in the Opening Night scene. This was written in a more traditional manner with me creating vocal lines which gave the impression of the singer almost improvising them, supported by a simple orchestral accompaniment. When this scene reappears at the halfway mark, and the action then rolls forward into the aftermath of the play and the howling reviews, I wanted to try a different approach. Here I again scored vocal lines which served the text dramatically; however, I didn’t score any accompaniment. Instead I asked the singers to each record all their lines as solos, with no direction from me as to how they should be delivered. The choices of speed, pacing, inflection and emphasis of delivery were all up to them. When the singers were happy, they settled into the version of each line they felt worked best, and I then took these away and scored an orchestral accompaniment around them. I think the result is highly effective, with the orchestra responding to the meandering and questioning nature of the vocal lines, and adding to the sense of distressed contemplation. Dramatically we are in a limbo world with half of our awareness focused on the real aspect of the characters writing their diary in front of us, and the other half being dragged into the swirling thoughts themselves. The music of the liminal space attempts to heighten this sense of the in-between for the audience.

Fig. 8 : Sophie Goldrick as Katherine Bradley in Veritable Michael, The Brunel Museum, 13th August 2022. Photograph by Ruth Knight.

Giving voice to Michael Field: perspectives on performing Veritable Michael

By Sophie Goldrick

As an opera singer, I spend much of my time inhabiting characters that are not real people, sometimes not even ‘people’: goddesses, sorceresses, cats and even chickens! These surreal or super-real characters often inhabit a theatrical world that is heightened, allegorical or inflated. Additionally, these works have been composed many, if not hundreds of years ago. To portray a real person, in their own words, to music that is hot off the press is an extraordinary situation for me to be in, and one that has been revelatory in many ways.

The choice of which voice would sing which character was an important one. In response to researching more about them: we read Katherine to be grounded, funny and steadfast, which felt like a good fit for the mezzo voice, which I have. This meant that I was going to be playing Katherine. By contrast, our Edith was more capricious, ethereal and prone to a little melodrama – so, naturally, a soprano.

On the surface I had a fairly superficial understanding of Katherine Bradley as a staunch, posh lady who liked big hats and unruly dogs. Conversations with academics and reading the diary were the keys to unlocking a deeper understanding of her. Katherine was fierce, idealistic, protective and surprisingly sentimental. In her two solo vignettes, Katherine’s letter to Robert Browning (1884) and Tom’s setting of the poem The Forest (1897), Tom was expertly able to capture these opposing forces within the character.

Tom and I discussed how the Browning letter felt like Katherine was storming up and down corridors and slamming every door on the way. You can hear this in the orchestration. Browning had threatened the safety of Katherine’s love and art, and she would destroy anyone who put that at risk. By contrast, The Forest is a remarkable gesture of love and comfort to Edith. It paints a picture of the natural world gathering around to honour and protect the body of James, Edith’s father, after his fatal fall from an Alpine cliff. Here the tone is meditative, warm and reverent. It was important that we include as many aspects of these two women as possible, to allow them to be both heroic and flawed. We did not want to shy away from the parts of their story that might be troubling, and still wanted to celebrate their triumphs and mourn with them in their defeats.

A particular aspect of our collaborative process worth highlighting is when Tom gave me a melodic guide to a piece of prose text, which we then workshopped with a focus on how to phrase it, before recording the one we liked best. I returned later to hear a new underscoring of that recitative, which Tom had created in response to the sung line. This was a first for me, and it also meant that delivering these recits was as close to speaking as singing could be. These sections are among my favourites in the opera.

The crucial part of giving voice to Michael Field was the other half of the whole, the soprano who would play Edith Cooper. Tom and I talked about a lot of singers we knew and admired, but we both recognised Lizzie Holmes as a great collaborator as well as a wonderful artist. We needed somebody willing to experiment and invest in a project that wasn’t yet fully formed. Lizzie was enthusiastic from the outset, and we knew it was the right choice.

Once Lizzie was cast, we were able to finally get to work on the most sweeping and romantic music in the piece: Katherine and Edith’s duets. If we had ever wondered ‘Why Opera?’ as the medium of this story, the ability of a duet to make our voices greater together than alone, answered that question. No other medium can better allow two people to speak as one as in music. The poem ‘It was deep April’ (1892) is a perfect example of this union. This is the first time we hear Katherine and Edith singing the same words together and so is when the united voice of Michael Field is first heard. While Katherine is written for mezzo and Edith for soprano, the range of Deep April is very similar for both of us, with the voices singing in unison and then moving apart, twining around one another and calling and responding. This movement between unity and harmony reflected something of the way Katherine and Edith created their work together as Michael Field.

Fig. 9: Patrick Neyman as Michael Field in Veritable Michael, The Brunel Museum, 13th August 2022. Photograph by Ruth Knight.

Staging Veritable Michael

As Tom mentions above, Veritable Michael won the Stephen Oliver award for best new opera in 2021, and the prize was intended to support a live performance. This led us on to the next stage of development after the podcast.

Our first challenge was to reimagine the voice of the host /narrator that I had performed in the podcast and instead create a character that belonged in the story and who could guide the audience through as it progressed. We thought that it would make sense to bring to life Michael Field as an onstage entity: a male avatar who could be part of and comment on the unfolding story.

Tom and I collaborated on this libretto, but the tone for this character was not easy to arrive at. We wanted Michael Field to be strange and poetic. We also wanted them to discover the nature of their identity along with the audience. Many editions of the libretto were written and tweaks continued throughout the rehearsal process.

We engaged a brilliant young director, Ruth Knight, to work as a co-director with the whole ensemble to create a live version of Veritable Michael in the summer of 2022. Staging the opera allowed us to knit it together in real time, as it had been recorded over a period of months for the podcast; however, it also tethered the work to a physical reality, where it had previously only lived in our imaginations. Tom’s ability to conjure different environments through foley was a magical part of the podcast opera, so we elected to keep our staging very simple and allow the sound world to represent the changes in location and time. We used costuming to give a sense of the era and an array of props and a pair of suitcases stood in for nearly every location: theatre box, train carriage, or restaurant.

Fig. 10: Lizzie Holmes as Edith Cooper (left) Sophie Goldrick as Katherine Bradley and Patrick Neyman as Michael Field in Veritable Michael, The Brunel Museum, 13th August 2022. Photograph by Ruth Knight.

Fig. 11: Lizzie Holmes as Edith Cooper (left) and Sophie Goldrick as Katherine Bradley in Veritable Michael, The Brunel Museum, 13th August 2022. Photograph by Ruth Knight.

Veritable Michael is a Shadow Opera production. Music by Tom Floyd. Words by Michael Field. Created and produced by Sophie Goldrick and Tom Floyd.

The complete podcast is available through Apple Podcasts, Spotify or the Shadow Opera website.

Performances by Lizzie Holmes, Sophie Goldrick, James Long and Patrick Neyman.

Co-directed by the company and Ruth Knight. Thanks to our contributors, Prof. Marion Thain, Prof. Carolyn Dever, Dr. Ana Parejo Vadillo, Dr. Sarah Parker. and Prof. Sally Marlow.

Veritable Michael was made possible by the Ralph Vaughan Williams Trust, The Stephen Oliver award, The Countess of Munster Musical Trust, King's College London and our team of crowdfunders.

For more information about the podcast and the team, visit www.shadowopera.com